A few weeks ago, we looked at the location used by the 50th New York Engineers during the Civil War. Today, we will look at the continuing history of this part of Capitol Hill.

A few weeks ago, we looked at the location used by the 50th New York Engineers during the Civil War. Today, we will look at the continuing history of this part of Capitol Hill.

Almost immediately after the sale of the leftover buildings of the Engineer Camp, the land thus freed up started to be built up. The Washington Evening Star of March 31, 1866 described the work as an “Improvement of Pipetown,” though they give no indication who gave it this name or why. The principal builder was a local coal and wood dealer named Thomas E. Clarke – or sometimes T. Edward Clark, or some other combination of these names. As the multitude of names indicates, Clarke seems to have been a somewhat dodgy individual, with local stalwart George A. Bohrer having taken him to court over $727.82 the previous year. (The following year, they would meet in court under slightly different circumstances, when both were summoned to the John Surratt trial as potential jurors; Bohrer was selected, while Clarke was not.)

Pipetown, like most neighborhoods, was not well defined, but it seems to have been the land west of 12th Street and south of K Street, southeast and extending down to the Anacostia River.

The whole area was somewhat insalubrious, with a policeman tasked with protecting the area sarcastically pronouncing that his “beat [was] a daisy.” He explained, according to the Washington Evening Critic of March 1, 1883, that the beat “cover[ed] one hundred and fifty squares, including Pipetown and the swamps and gullies of the eastern commons.”

In fact, the only time that Pipetown appears in the news is when something terrible has happened. For example, in 1887, a Louis Bowman was arrested for having fired his gun numerous times while in Pipetown.

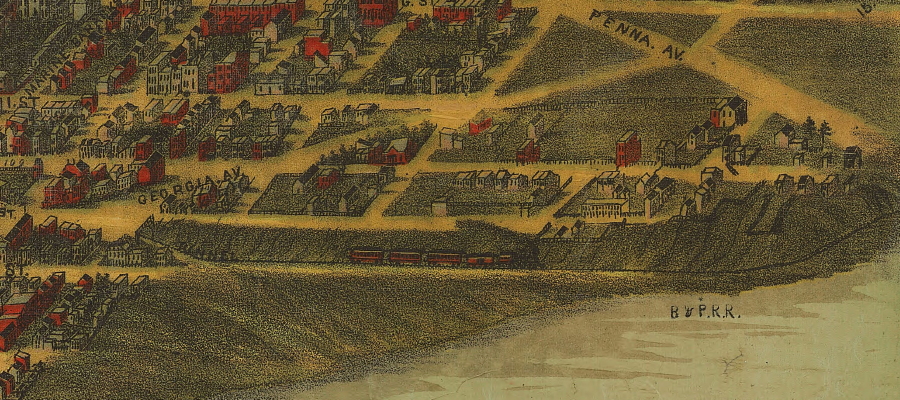

Birdseye view of Pipetown ca. 1888. Detail of a Adolph Sachse map. (LOC)

There were stories that showed Pipetown in a slightly different light, even if they did stem from the appearance of numerous of its younger inhabitants in court. For instance, there was the story that went through the newspapers about ten years later. It began with a complaint from a Mrs. Garrison, who stated that a number of young men had been “hooting and swearing and raising cain generally” in front of Fred Schlosser’s place on the corner of K Street and Georgia (today Potomac) Avenue. The occasion of this sort of carrying on had been a rope-jumping tournament. Nonetheless, the young men were placed under arrest and ordered to appear before Judge Ivory Kimball.

According to the Washington Post of March 27, 1892, the “court resembled a kindergarten school yesterday morning” when a dozen “youthful disturbers” had been brought up. Remarkably, the boys were represented by counsel, in the form of Belva Lockwood (pic), who had “ceased nursing her little Presidential boom to appear in court.” This snide editorializing by the Post was actually quite wrong – while Lockwood had indeed run in the previous two elections, she did not do so in this one, nor would she again.

Lockwood’s defense was to question each miscreant separately, and elicit only that they had “only skipped the rope and had not shouted.” Kimball “could not believe that such a collection of cherubim could exist outside the pearly gates, certainly not in South Washington, and warned Mrs. Lockwood to that effect.”

In the end, while she did manage to get two of her young clients off, the others – and Mr. Schlosser – were forced to pay a fine of $5 for their exuberance.

Next week: More on Pipetown.