We encourage our readers to submit opinions on subjects about which they are passionate, especially if they are related to our neighborhood and our neighbors’ quality of life. Interested in voicing your opinion? Send us an email at info@thehillishome.com –María Helena Carey

By Lindsey Jones-Renaud with Karen Smith

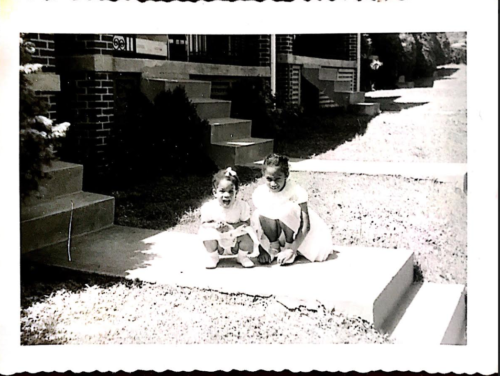

When my neighbor Karen Smith and her friends would roller skate around the Kingman Park neighborhood of Washington D.C. in the 1950s, they would dream about their neighborhood achieving historic notoriety, like nearby Capitol Hill. “We would fantasize about renaming the streets to reflect the beauty of the mostly white neighborhoods we could see, but couldn’t dream of living in,” she explained. Almost 70 years later, in May 2018, Kingman Park has been designated a historic district, just like Capitol Hill. Karen is honored to be a part of it: “Historic designation is the closest thing to that reality, [something] that I never thought would happen to a Black neighborhood in Washington D.C.”

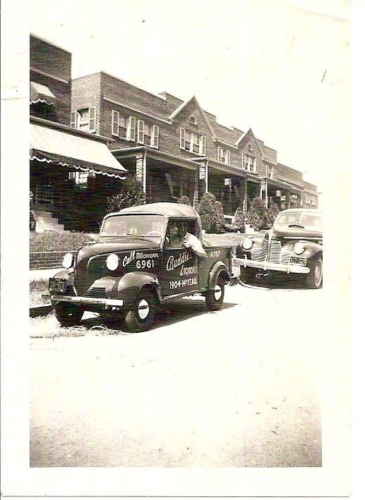

Karen’s grandfather, Edwin Leak, in his car in front of his home in Kingman Park, 1940s-50. Photo courtesy of Karen Smith

Of the 34 neighborhood historic districts in Washington, most have a social history that reflects the achievements of white Americans and a few present multiracial histories. But in Kingman Park, the founding homeowners were exclusively African American. Despite forced segregation until the mid-twentieth century and redlining in later decades, black families like Karen’s grandparents built Kingman Park into a prosperous community. It is this history that the applicants of the historic district sought to preserve. It is the first neighborhood in Washington DC that has received historic designation because of its African American history.

Yet, the Kingman Park Historic District did not pass without controversy, which was amplified by the voices of Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner Bob Coomber, who represents much of the residential area that was designated a historic district, and the blogging platform Greater Greater Washington. Even though the Kingman Park fight is over, Coomber and Greater Greater Washington are leading a new fight to change the historic district process in a way that could, in effect, give the power to determine how to recognize historically African American neighborhoods to predominantly white residents who have moved in as part of a wave of gentrification. In this piece, I provide an alternative perspective in an attempt shed light on the racialized implications of these reform efforts.

Opposition to the Kingman Park Historic District

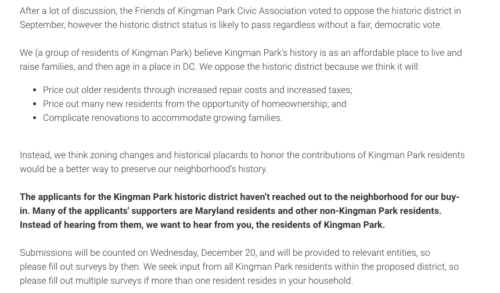

Coomber and Greater Greater Washington argue that the Kingman Park historic district was approved even though, they claim, there was a significant majority who opposed it. The reality is that we don’t actually know if a majority opposed or supported the designation. The data that they cite as evidence against the district came from a non-scientific survey that Coomber and other opposers designed and distributed to households in the neighborhood. In reading through the survey, the bias toward opposing the district is clear right from the beginning where they state, “we oppose the historic district,” and then ask respondents if they agree with their statement. The survey also did not attempt to understand the nuances behind the opposition. For example, would residents support historic designation if the perceived financial and time burden could be mitigated through government and community subsidies? From what I have observed, opinions about historic designation have fluctuated and evolved over time as more information became available. My husband and I, for example, initially responded to the survey that we opposed the designation, but when the Historic Preservation Office (HPO) released its first report in January 2018, we both changed our minds. Smith, had a similar experience, where she initially participated in the movement to oppose historic designation, but then read the HPO staff report and ultimately decided to support the application. Unfortunately, the oft cited survey data, which was collected in December 2017, was never updated to reflect how opinions like ours may have shifted over time.

Screenshot of the survey that Coomber and other opponents circulated to assess support for or against the historic designation. They also circulated a paper survey that used different language.

Whose voice matters?

The question about whether or not there was a majority in opposition also depends on whose voices counts during the process. Coomber, who is white, and other opponents – including some African Americans– often argued that the voices of non-residents should not count in the designation decision. They used this claim to minimize the credibility of many historic district proponents, including the applicants. In his recent op-ed, Coomber writes, “the applicants did little or no outreach to neighbors. Instead they solicited support from people they knew, many of whom do not even live in the neighborhood anymore. Comments of support came in from people who live in Maryland and even California.”

This repudiation of the voices of people who do not live in present-day Kingman Park was repeated several times during both hearings. One resident, who recently purchased a home in Kingman Park and does not appear to be of African American descent, said: “We want to make sure the voices of the people who own the property… are listened to and heard.” Another resident, who appears to be from a similar demographic as the first, said, “as people who have chosen to spend our adult lives and physically and financially invest in the District of Columbia … our voices are more important than that of Maryland residents who have decided to spend their adult lives somewhere else.”

While there were indeed many people who submitted public comments in support of historic designation but who reside outside of Kingman Park, according to a report from the HPO, most of these supporters either grew up there, had family who lived there, attended schools within the historic district, or have family still living in the neighborhood. As part of its assessment of whether a proposed neighborhood fits the historic designation criteria, the HPO allows for and reviews public comments from anyone, regardless of where they live.

What the opponents to historic designation appeared to be saying is that even people who are directly connected to Kingman Park’s history should not have a role in determining how to preserve that history, unless they presently live here. According to opponents, if an individual has physically left Kingman Park, their voice no longer matters, even if they still consider the neighborhood their home.

A few weeks prior to the public hearing about historic designation of Kingman Park on January 25, 2018, Coomber and the other opponents circulated a flier that tried to rally the community against voices of non-residents. Kingman Park resident Rica Rich, a legacy homeowner whose grandparents purchased property here during the founding decades of the neighborhood, read the flier at the hearing. She read: “Non-resident views have influenced the claims about our homes… However, there is still hope for the voices in our community to be heard.” She later told me how upsetting that flier was to her. “I saw that letter saying ‘save our community’ [and I thought] how about you come in and have a conversation with the people that are already here – who have kept the neighborhood alive for 70 years so that you have a home to purchase at a discounted rate [compared to other homes in Washington DC]? But instead you’re just going to come in and kick us to the curb and say now we have to follow your rules.”

The people who left Kingman Park are its history

Listening to Karen tell me her family’s story, I learned about how the movement of African Americans from Kingman Park to other neighborhoods, cities, and states – and back again – is a central part of its history. “Speaking to people being outside of Kingman Park, migration was a natural progression for Blacks,” Karen explains. She elaborates that her grandparents purchased her present-day home at a time when redlining and segregation restricted African American ownership and movement across the district. “Living in this area was the first time that many African Americans could call themselves a neighborhood and a community. Because every time they went somewhere else they got pushed out. White folks did not want to live here.” But as integration laws changed to allow African Americans more opportunities to live in different areas, many moved. Moving was an exercise in their newfound freedom; a freedom that, up until that time, had been exclusively afforded to white people.

African American families like Karen’s built up Kingman Park and accumulated wealth through homeownership so that their children would have greater opportunities beyond their neighborhood. Karen recalls how “the District was so small that Black families had limited resources and services. [The conditions] were usually better than those in nearby rural areas of Maryland, but overall they were limited. So upward mobility and further education eventually took you out of the District.” By including the voices of non-residents who have a historical connection to Kingman Park, the Historic Preservation Review Board showed that it values the contributions of former residents to DC’s history. As Karen says, “I believe the designation will help those whose families were here be remembered for their contributions to DC.”

Who gets to decide how to preserve African American history?

It can be difficult for Americans – especially white Americans like me– to look beyond the link between land ownership and voice. It is in the very DNA of our country. From the beginning of the United States, the people who owned the land and the property were the ones who had the right to vote. Only their voices mattered. However, when it comes to preserving the history of a minority group, the powerful majority should not always be the sole deciders. Historically, the folks who have wielded wealth and power have not been very good about honoring the contributions of the less powerful, especially when it comes to racial minorities.

In Coomber’s survey, many residents who opposed the creation of a historic district checked a box that expresses a preference for other ways of remembering Kingman Park’s history, such as historical walks. Such “alternatives,” however, also happen to be more convenient and easy to ignore if you are a current resident. Are we truly honoring history if we aren’t willing to safeguard its physical integrity? At the Historic Preservation Review Board hearing on April 26, Dr. Patricia Fisher who is a third generation Washingtonian and lives in nearby Capitol Hill explained this perspective saying, “We should not have to depend on oral history. We should be included in all of the historical documents and recognitions that this city has. We have paid a price. We have contributed. And we should not be treated as second class citizens–and as a footnote in terms of historic districts in this city.”

Reducing the burden of historic districts on seniors and under-resourced neighbors

Another argument that has been made against the historic district was that new requirements and approvals would impose burdensome regulations on homeowners. In his recent op-ed, Coomber pointed to research from other cities and contexts that shows historic designation being correlated with an increase in property taxes. In the Kingman Park context, however, where the median listing price of homes in has already increased more than 50% in the past five years, this argument doesn’t carry much weight. With skyrocketing prices home values, the HPRB spoke about historic districts as stabilizing forces during periods of economic fluctuation. The applicants too made this argument during the hearings. In this light, the resistance against the historic district could be interpreted as a veiled argument for the acceleration of gentrification, but without any requirement for respecting the history of the community.

In speaking with Karen about the future of Kingman Park, she wondered, “What would this neighborhood become if it wasn’t designated historic? If an influx of more affluent residents were allowed to make massive home improvements and the area became real estate investments rather than a community neighborhood? Would that not induce a mass exodus of the African American population that now exists here?”

Safeguarding marginalized and minority voices

African Americans in Kingman Park deserve to have their neighborhood history preserved just as much as white Americans do in Georgetown and Capitol Hill. The fact that one group may have fewer resources to invest in historic preservation than the other is not a reason to deny them this distinction. In fact, we must acknowledge that this resource inequality is a product of the same oppressive policies that led to Kingman Park’s establishment as an African American neighborhood in the first place.

Since Kingman Park’s historic district status was approved, Coomber testified in a June 21 public roundtable with the DC Council calling for democratic safeguards to be added to the historic preservation process, with an assumption that only current homeowners are included in this democracy. Similarly, Greater Greater Washington is circulating a petition to get the DC Council to take up this issue, calling the outcome of the Kingman Park historic designation an “abuse” of the process. This narrative is troubling. Instead of only valuing the preferences of new, majority-white residents, historic designation processes for neighborhoods with rich African American histories must respect the voices of the people with direct ties to that history, even if they no longer have a physical address there.

Lindsey Jones-Renaud is a white resident of Kingman Park where she has lived with her husband and children since 2012. You can find her on Twitter @LindseyJonesR. Learn about the historical context of Kingman Park in the Historic Preservation Review Board’s report here (https://tinyurl.com/ydgjocwv)