On this Emancipation Day it is appropriate to look at the story of one man who was freed because of Lincoln’s signing of the D.C. Emancipation Act on April 16, 1862. His name was Philip Reid. While you may not know him, you see his work every time you look at the Capitol.

On this Emancipation Day it is appropriate to look at the story of one man who was freed because of Lincoln’s signing of the D.C. Emancipation Act on April 16, 1862. His name was Philip Reid. While you may not know him, you see his work every time you look at the Capitol.

I have previously written several times about the Statue of Freedom on top of the Capitol Dome, but never got around to writing about its most important chapter: that of its casting here in Washington D.C. at the foundry of Clark Mills (pictured).

After the plaster version of the statue, as executed by Thomas Crawford, arrived here in Washington, the five sections were put together and placed in the old House of Representatives chamber. The gaps between the pieces were covered with plaster, such that it would have the appearance it would eventually have after casting. Difficulties began when it came time to take the statue apart again to cast the individual pieces: The man Mills had hired to put together the statue in the first place demanded a doubling of pay in order to take it apart. Mills refused to pay; however, he then had to figure out how to do it without the man’s knowledge.

Fortunately, Mills knew someone to whom he could turn: Philip Reid. Reid had been working for Mills since Reid had bought him in South Carolina around 1830. Mills brought him to D.C. when he was given the contract to cast the statue of Andrew Jackson that still stands in Lafayette Square, across from the White House, and both had remained here since.

Reid’s plan was simple and ingenious: He connected a rope to the ring at the top of the statue, then used a simple crane to pull up on it. This separated the pieces just enough to show where the seams were, and thereafter, work was straightforward.

The casting took about a half year of working seven days a week, which meant that Reid actually earned money for himself in that time – all pay for Sunday work went to him, earning him $1.50 each week. The casting was completed by the end of 1861. In early in June of the following year, the first two sections were transported to the Capitol grounds. While the Capitol dome was far from ready, Mills wanted, according to the Alexandria Gazette “to surrender the work to the protection of the Federal authorities.”

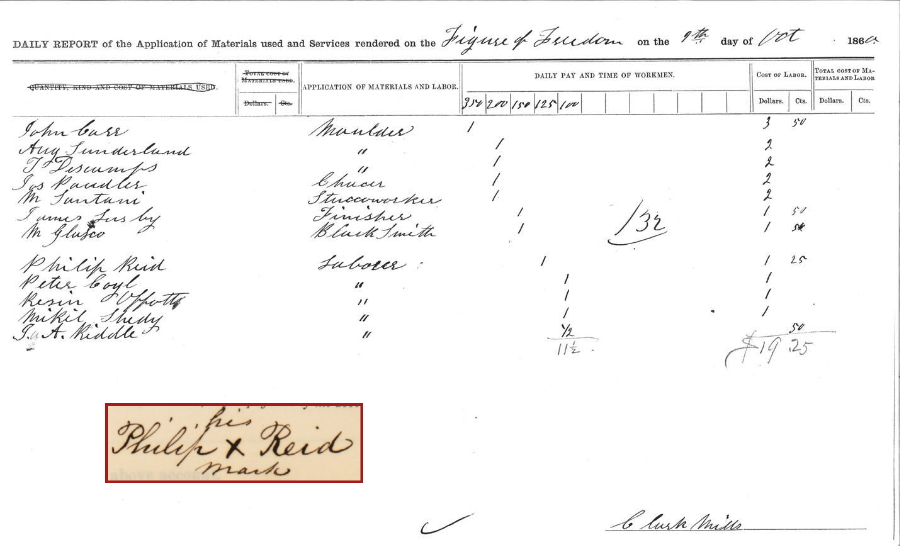

Payroll report showing Reid’s pay for October 9, 1860. Insert is his mark from a pay voucher. (AOC)

Much had changed in the intervening months. On April 16, 1862, Abraham Lincoln had signed the D.C. Emancipation Act, which had freed Philip Reid. In accordance with the act, Mills filed a petition with the emancipation commissioners, requesting compensation for his lost property. By far, the newly freed person that he demanded the most for was Reid – a stunning $1,500 (over 40,000 2018 dollars). Mills would only receive $350.40, which was slightly above the average paid out.

The statue of freedom was not placed on top of the Capitol until late 1863, with the final piece being added on December 2. Whether Reid witnessed the final triumph of his work is not known. He did, however, remain in Washington thereafter and was “highly esteemed by all who [knew] him,” according to a guide published after the war.