Last week we looked at Alexander McCormick, Capitol Hill merchant. The McCormick family stayed nearby, starting with his son, also named Alexander McCormick. The younger McCormick was, like his father, not one to make it into the history books; however, two tales of his life are worth mentioning.

Last week we looked at Alexander McCormick, Capitol Hill merchant. The McCormick family stayed nearby, starting with his son, also named Alexander McCormick. The younger McCormick was, like his father, not one to make it into the history books; however, two tales of his life are worth mentioning.

The first was that McCormick, who was a lawyer, also was one of President Millard Fillmore’s (pictured) private secretaries. Given that Fillmore is hardly one of our more celebrated chief executives, McCormick did not achieve the renown of, say, a Nicolay or a Hay because of this. Nonetheless, a number of papers are signed by McCormick in Fillmore’s name have survived.

Much more interesting is an episode that happened about ten years later. McCormick had bought property that he called Vandalusia. This spread, named after the homeland of the Vandals, had the odd distinction of being partly in the District of Columbia and partly across the border in Maryland. McCormick used this quirk to his advantage after April 16, 1862, when President Lincoln signed the D.C. Emancipation act. News of his dealings came to the ears of the commissioners who had been hired to implement the act, and they had a supplemental act passed to counteract McCormick. In their supplemental report, they explain:

It appeared in evidence that Mr. McCormick, being a citizen of the District of Columbia and the owner of these slaves removed them into Maryland a few days before the emancipation act became a law. His farm is immediately on the line, and lies partly in the District of Columbia and partly in Maryland. He built a small tenement a few rods beyond the District line and put the servants in it, while his own dwelling was on this side of the line, together with the cow-pen and whatever pertained to the homestead.

The pasture extended on both sides of the line, as did other enclosures in which the servants were required to labor, but with instructions that they should not cross it into the District of Columbia. It was proven that Alice was required to drive the cattle from the pasture to the cow-pen, under the injunction, however, not to cross the line. It was also in evidence that the daily food of the servants was sent from the residence of Mr. McCormick, generally by some member of his white family; and when it was not thus taken to them, there was no alternative but for the servants to go for it, or to fast. This frequently happened, and they often came across the line to their master’s house for the necessaries of life.

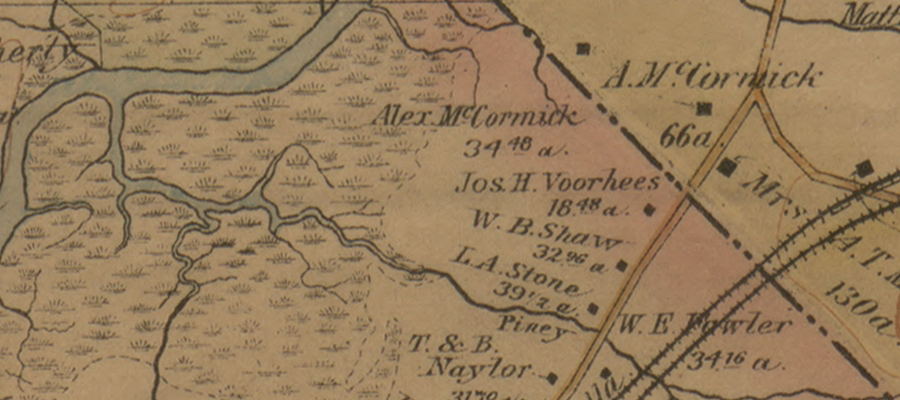

Deatail of an 1878 map of the District of Columbia, showing McCormick’s property. On the left is the Anacostia River, on the right is Kenilworth Avenus. (LOC)

In short, the commissioners did not see the situation the same way as McCormick and he was required to comply with the Emancipation Act and free the five enslaved people that had sued for their freedom.

McCormick was married twice: first to Elizabeth Van Horn, with whom he had four children; and then later to Elizabeth Truman Young, with whom he had a further eight. He died at the ripe old age of 89 in 1891. He was buried in Congressional Cemetery, near his two wives and his father.

His estate is today, on the D.C. side, a piece of wooded land near Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens. On the other side of the District line, it is a WSSC property that contains one small clue to its origins in the name of the road that snakes through it: Andalusia Lane. What happened to the ‘V’ is anybody’s guess.