My look at Bloodfield last week focused on the lawlessness that prevailed there –for the simple reason that this was what the newspapers of the time reported. Occasionally, however, there were also hints of the abject poverty that afflicted those who lived there.

My look at Bloodfield last week focused on the lawlessness that prevailed there –for the simple reason that this was what the newspapers of the time reported. Occasionally, however, there were also hints of the abject poverty that afflicted those who lived there.

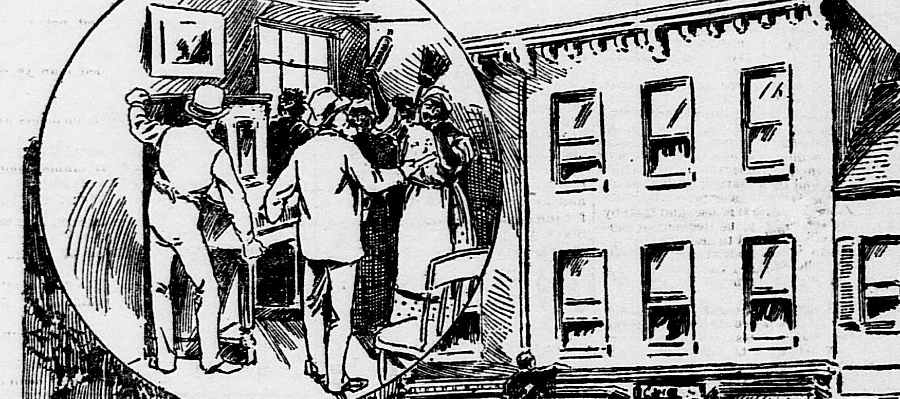

For instance, just a few months after the piece on the tallest policemen, the Morning Times did a piece on the constables of the city. These men had no power of arrest in the District, but were responsible for repossessions and ejections of recalcitrant tenants. A reporter followed them along on their rounds one day and one of the incidents occurs in Bloodfield, where the constables were to repossess a parlor organ:

The constable and his deputy quickly got into the shanty through a rear door, only to be confronted by two colored women, one of them a veritable giantess, over six feet tall[.]

Swinburn forced the door, against which this mountain of flesh had placed herself, only to find himself in a human vise. The big female wound her muscular right arm about his neck and nearly squeezed the breath out of his body. Finally, as she had nearly succeeded in shutting off his wind, the constable wriggled loose from her grasp.

He then yelled “Police! And two patrolmen came to his rescue. They rushed in, and the battle for possession of the organ commenced. Swinburn came out victor. He secured the property, placed it in a wagon, and returned it to its lawful owner.

Occasionally, the news from Bloodfield was a bit more heartwarming. This is the case of the stray dog named “Dr. Tanner” who would follow the patrolman on his beat. Dr. Tanner would be caught by dogcatchers, but locals would raise whatever money was needed to get him out of their clutches and return him to the street.

Both of these stories were published in 1896, the same year that a major change in the policing of the area was announced. The Washington Evening Times of Dcember 11 ran a stories headlined “Colored Policemen Only: ‘Bloodfield’ to be Patrolled by Them Exclusively Hereafter.” While the hope was that they would be more effective than the white policemen who had previously walked the beat there, the change had been triggered by the recent death of an African American preacher named London Shears by a policeman.

Detail of a picture entitled “Trials of a Constable” and illustrating the repossession of the parlor organ. (LOC)

The bad news from Bloodfield hardly let up because of this change, with fights – in one case between a Bloodfield gang and a visiting circus – being daily occurrences, as well as smallpox outbreaks, and assaults on policemen.

While the area did settle down after the turn of the century, it was still referred to with some distaste all the way up the first World War, and stories of cops would often mention that they had started off patrolling its mean streets – for instance Officer Headley (pic) would who would be thus honored in 1906.

By 1917, though, Bloodfield was a part of history. That year the Washington Herald published a poem by C. H. Turnbull entitled “How Times Have Changed” and describing an attack by a group of youths on the narrator. He escapes to a grocery store, where the proprietor tells him that he should have seen the place “’Way back in eighty-one!” but that times have changed:

But now they’re sort of peaceful lie, and there is no complaint!

When brushing off my ruined clothes, I said “The h–ll there aint!”