Two weeks ago, I wrote about John Westfall and how he saved Abraham Lincoln’s life during the latter’s second inauguration, and how Westfall was promoted to Lieutenant due to his actions. Today, we’ll look at the –remarkably tame– aftermath of this remarkable story.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about John Westfall and how he saved Abraham Lincoln’s life during the latter’s second inauguration, and how Westfall was promoted to Lieutenant due to his actions. Today, we’ll look at the –remarkably tame– aftermath of this remarkable story.

For the next ten years, Westfall remained a Lieutenant in the Capitol police. He and his wife lived at 501 C St SE, on what is today Seward Square – and right across from where Trinity Methodist Church would be built many years later. He also owned a house one block east of that and was active in the Fifth Ward Building Association.

Westfall’s quiet tenure at the Capitol police would come to an abrupt end on March 1, 1876. With all of two weeks notice, he lost the job that he had held for s 15 years. Why this happened is unclear, but it did bring up the story from long ago. In the following month or so, not just Belshaw, but five others who had been in the Rotunda on that day gave affidavits that all concurred in their assessment of Westfall’s actions that day. There was even a number of newspaper articles published during this time praising Westfall, such as this one from the New York Tribune (and republished in the Daily National Republican)

[Booth] was discovered by a member of the Capitol police – Mr. J. W. Westfall, of New York – who on several occasions before, as well as since, has given evidence of his faithfulness and efficiency. He seized the excited stranger, and, after a severe struggle, during which Major. B. B. French, then Commissioner of Public Buildings, at the suggestion of Mr. Westfall, caused the door to be closed and aid to be furnished, succeeded in forcing him back into the crowd.

None of this was enough to get Westfall rehired. Westfall then worked in D.C. as an “overseer” –though it is unclear who or what he was overseeing. However, by 1880 Westfall had moved back to Dutchess County, New York, where he worked as a bookkeeper. Nonetheless, he couldn’t stay away from the nation’s capital, and so by the mid 1880s, he was back working as a copyist at the Patent Office, earning $60 a month, less than half of what he was earning as a police lieutenant ten years earlier. Even worse, he lost this job the following year. What he did for the rest of the 1880s is unclear, though he was a member – and even librarian – of the New York Republican Association. At this time his wife found work, working as superintendent of the Washington Directory for Nurses and later as the matron at the Washington Training School for Nurses.

In the early 1890s, he once again found work, this time as a watchman for the Smithsonian Institution. This dropped his salary to a pitiful $50 per month. In this time, he and his wife lived in northwest D.C., but toward the end of the century, he moved back to Capitol Hill, and it is here that he is listed for the last time in a census, at 235 C St NE. His wife is not shown to have a job. The census record also reveals the tragic detail that of the three children the two had in their life, none was still alive. In fact, as best can be gleaned from other records, none lived more than a few years.

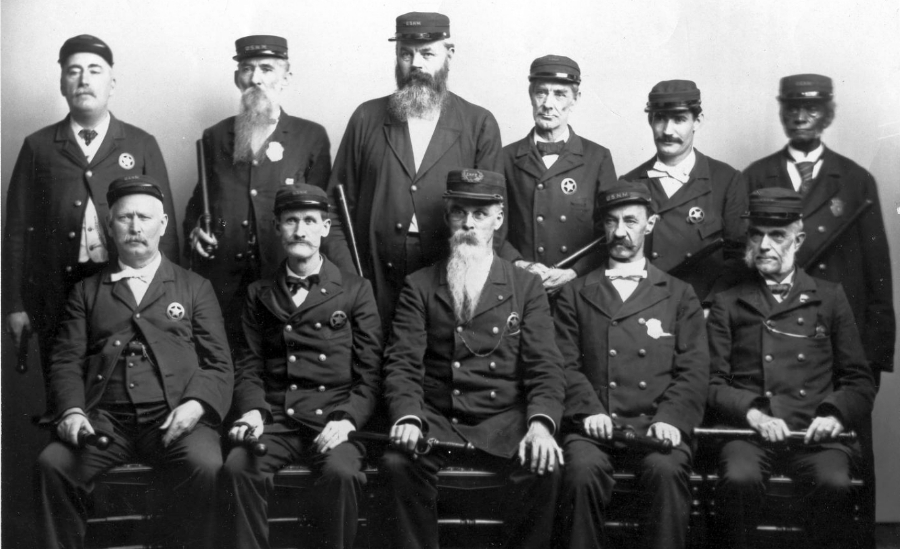

Westfall and his colleagues at the Smithsonian. He is all the way on the right in the first row. (Smithsonian)

During this time, Westfall was also photographed alongside his fellow Smithsonian watchmen. Sporting an impressive pair of muttonchops as well as dark eyebrows, and holding a nightstick firmly on his lap, he looks to be able to give miscreants a run for their money, in spite of his advancing age.

On April 26, 1901, the Evening Star laconically mentioned under the headline “Deaths in the District” that among the deaths “reported to the District health department during the twenty-four hours ending at noon today” was “John W. Westfall, 73 years.” No further mention of him was made. He was buried in the town of Amenia, in Dutchess County.

A few months later, in the course of an article in the Washington Post about Ward Hill Lamon and the difficulties in protecting Lincoln, Lamon mentions the scene during the second inaugural and how Westfall had “thrust [Booth] bodily from the passage leading to the platform reserved for the President and his party.” It was as close to an obituary as this quiet hero would have.