I wrote of the Experimental Model Basin last week, and mentioned some of the tests that had been done there for the Navy. The basin was, however, also used by private citizens, as we will see in today’s episode.

I wrote of the Experimental Model Basin last week, and mentioned some of the tests that had been done there for the Navy. The basin was, however, also used by private citizens, as we will see in today’s episode.

Stopping a ship has always been a problem. Anyone who has ever tried to smoothly berth a sailboat alongside a dock will immediately appreciate the difficulties faced back in the days of sail. With the advent of steam propulsion and propellers, it did not get necessarily easier. While the option now exists to reverse the propellers, this does not have the desired effect: the action leads to cavitation and a loss of all power. Enter John Harold Hyde (pictured at left) and his ship brake.

Hyde had been born in Michigan in 1870, but moved with his family to Washington State in 1884. After stints in the printing, timber, and mining fields, Hyde was impelled by the Titanic disaster to take up ship engineering, and, in particular, a way of stopping ships quickly.

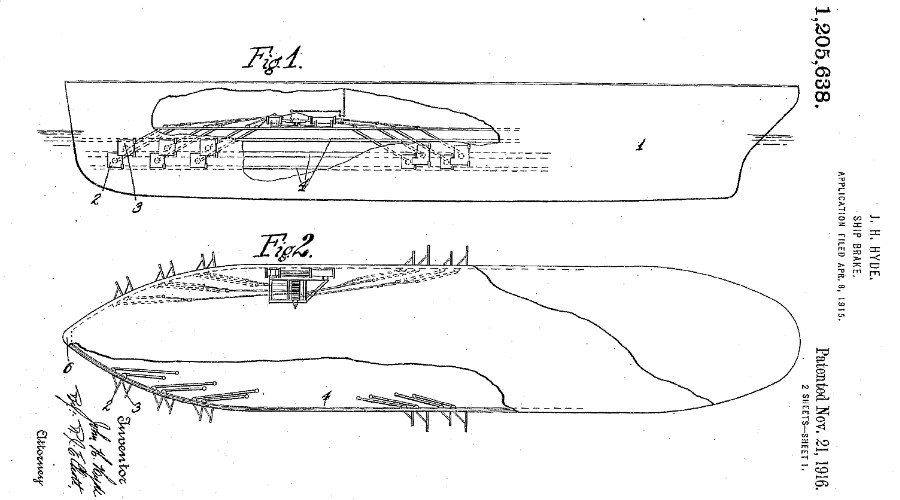

The idea was pretty simple: a series of flaps on the bottom of the ship that could be flipped out to increase the drag on the ship and stop it short. The first full-scale test was done on a tugboat in the Puget Sound, and it seemed to work, though the ship was only going 8 m.p.h. when the brake was set.

Detail of one of the the patent applications submitted by Hyde (Google patent)

The next step was a more thorough analysis. This took Hyde to Washington and to the Experimental Model Basin. The tests began on August 10, 1915. On August 28, the Washington Herald published a long article describing the tests:

A model of a 4,200-ton passenger steamer was used, and resistance of the ship through the water went up by some 240 percent when the brake was applied. At around the same time Captain William Strother Smith did similar experiments, which he described at the Society for Naval and Marine Engineers [SNAME] later that year. While there is a decrease in the speed when the brakes are applied, the location of the brakes is critical, and the shape of the hull is crucial in being able to fit the brakes to it. His conclusion is that a brake is possible, but becomes entirely a question of whether it is financially viable, and while he carefully does not express an opinion, it seems clear that it is not worth the money or effort.

When he gave the paper, another member of the SNAME, Clay L. Jennison, announced that he was the one to have done Hyde’s experiments, and that he agreed with Smith’s conclusions. The only question was whether the Smith-tested brake had been added to the SS Empress of Asia as Smith had alluded to. Smith answered that it had not, and that was the end of the discussion.

It also seems to have been the end of any attempts to install a ship brake. Hyde disappears into the mists of time, and I can find no further references to ship brakes, either theoretical or practical, beyond this.