Today, getting to Washington DC is easy – the most difficult task is to decide which of the many modes of transport you will use to get here. And unless you get stuck in traffic, finding a route in is as easy as turning on Google maps. Obviously, it was not always thus, particularly in the early days of the city’s existence, when the nation’s capital was more notional than actual.

Today, getting to Washington DC is easy – the most difficult task is to decide which of the many modes of transport you will use to get here. And unless you get stuck in traffic, finding a route in is as easy as turning on Google maps. Obviously, it was not always thus, particularly in the early days of the city’s existence, when the nation’s capital was more notional than actual.

Fortunately, there have always been people willing to help you get here. In the early 19th Century, this task was taken on by Mathew Carey, a Philadelphia publisher. Carey hired the surveyors Joshua John Moore and Thomas W. Jones to determine how to best get from his hometown to New York, as well as to the nation’s new Capitol.

Moore and Jones – paid a grand $1 per mile surveyed – found it to be a most difficult task. It took them 12 days to make their way from Philadelphia to New York City, and arriving there, they wrote to Carey “We should have written to you before this, had not fatigue of our daily Journies rendered repose indispensable after the finishing of our Notes and Traverses.”

In spite of their complaints, the results – converted to maps by four engravers, and printed by Carey – were excellent. The resulting book, grandly entitled “Traveller’s Directory, or a Pocket Companion Shewing the Course of the Main Road From Philadelphia to New York and From Philadelphia to Washington with Descriptions of the Places Through Which It Passes, and the Intersections of the Cross Roads,” was an important document for those coming to the District to work. One can easily imagine New York Senator DeWitt Clinton being given this book in 1802 after being elected to serve out John Armstrong’s term, to make the 240 mile journey from NYC to DC a bit easier.

The bulk of the book is taken up by descriptions of cities and sights along the way, along with the tolls necessary to cross various rivers, either by bridge or ferry. Generally, only features directly next to the road are described, though at times, more interesting places a mile or so from the road are mentioned. Moore and Jones, who were also responsible for the text, sometimes struggled to make small, unimportant, towns seems interesting, and occasionally gave up. The description for Tully Town, Pennsylvania clearly shows the latter “Tully Town, at the twenty four mile stone, is an insignificant place.” Usually, though, they manage to find something to write, even if it is just that the town has “fifty or sixty houses.”

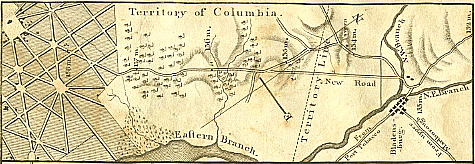

The last map, showing the trip into the District of Columbia. The scale is one inch to the mile. (Princeton University)

Of greater interest than the text, however, are the maps at the back, which work much as AAA’s now-defunct Triptiks: each stretch of the journey is shown on a narrow strip of paper with the road down the middle, and cross-streets, water courses, towns – and the occasional private house when there were no other features. A traveler would indeed know what was in store for him or her when using this, whether hills to be climbed or water to be traversed.

Even better, they remain as readable today as 210 years ago, and thus can be followed on any online map, and see how travel back then compare with trips today.

In future installments, I will describe some of these maps in greater detail, particularly the routes down into DC.