Today’s piece really should be called, “Hooray, the National Intelligencer is online!” Yes, the first run of this venerable newspaper, founded in 1800 as Washington’s paper of record, is finally available at the Library of Congress. The insights that can be gleaned about the early days of the nation’s new capital are invaluable. In looking through these issues, particularly in regards to the Washington Navy Yard, I was struck by a number of different things, one of which I will write about today.

Today’s piece really should be called, “Hooray, the National Intelligencer is online!” Yes, the first run of this venerable newspaper, founded in 1800 as Washington’s paper of record, is finally available at the Library of Congress. The insights that can be gleaned about the early days of the nation’s new capital are invaluable. In looking through these issues, particularly in regards to the Washington Navy Yard, I was struck by a number of different things, one of which I will write about today.

Rewards for the capture or information leading to the capture of someone are today the realm of the FBI’s most wanted list, or of police departments when a particularly heinous crime has been committed. In the early days of Washington, D.C., offers of reward were more of a daily occurrence, and the National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser often had multiple such offers.

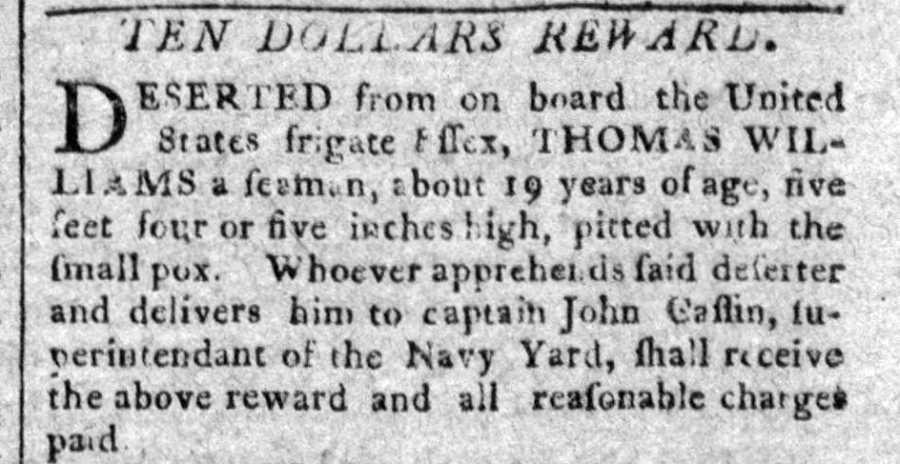

The most famous of these old advertisements were, of course, the missing slave notices; however,they were used for other types of situations as well. In the case of the Washington Navy Yard, they were almost invariably sailors AWOL from one of the ships visiting or laid up there.

A typical advertisement – and one of the earliest – is in the National Intelligencer of November 18, 1803:

John Cassin (pic) was Thomas Tingey’s second in command at the Navy Yard. (LOC)

To put the reward money into perspective, $10 in 1800 are $140 today, according to inflation calculators. However, pay at the Washington Navy Yard in 1811 (the earliest payrolls that have survived) was as low as $.15/day, though it was usually more like $.75/day at the low end, to a maximum of $2.00/day. So $10 would be a week’s pay for a skilled craftsman, jobs that today would command well over $1000/week.

The same advertisement also mentions that a Richard Davison of the frigate Congress, but currently in hospital, is also missing, and – presumably – would be worth the same amount to anyone apprehending and delivering him.

Why Williams – or Davison – would desert is not given. The Essex was currently being repaired, having returned from the Mediterranean the previous year, where it had taken part in the First Barbary War. It would return thence the following year. The USS Congress was decommissioned at that time, having last fought in 1800 during the Quasi-War with France. She, too, would be sent to the Mediterranean the following year.

So, it is possible that the two were simply bored.

Rarer were advertisements for missing apprentices. Daniel M’Dougal, a sail maker of the Navy Yard advertised for his runaway “apprentice lad” a few weeks later. John Melco was the young man’s name, and he was described as, “of effeminate appearance and much given to strong liquor.” Furthermore, M’Dougal cautioned “all persons at their peril, from harboring, employing, or carrying him out of the district.” The reward for Melco’s return was only five dollars, “but no allowance for expences. [sic]” This was still a pretty decent reward, in contrast to another where the offer is all of ten cents. In that case, one assumes that the advertiser was not really terribly interested in getting the runaway back again.

Today, the military does not offer rewards for the return of AWOL service members, unless they have also been accused of some crime.