I have previously written about visitors to the Washington Navy Yard. Today, I introduce another group: The first ambassadors to the United States from the newly opened country of Japan.

I have previously written about visitors to the Washington Navy Yard. Today, I introduce another group: The first ambassadors to the United States from the newly opened country of Japan.

In 1860, seven years after Commodore oorooatthew Perry had established trading with Japan, the Japanese government sent an ambassador to the United States, along with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce that had been signed two years earlier, but was now to be ratified.

It was a long trip for the members of the embassy, as the ambassador and his traveling companions were called. After stopping for a month in San Francisco, they had sailed to Panama, where they crossed the isthmus on the new railroad, then took the USS Roanoke from there to New York City.

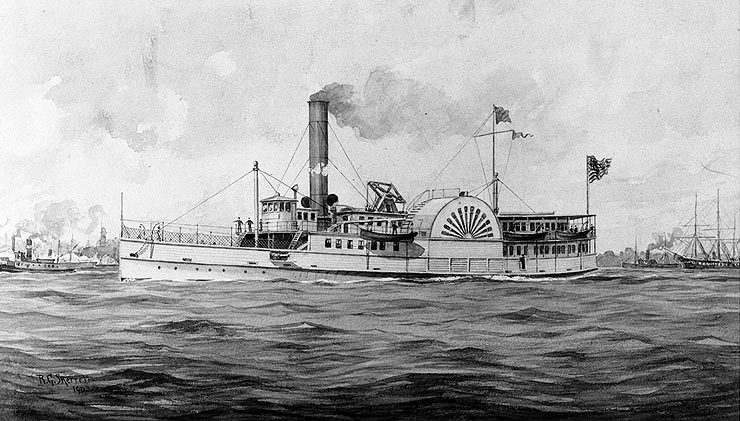

Just outside New York Harbor, near Sandy Hook, NJ, the Roanoke was stopped and told to return south and to Washington, so their first official meeting would be with President Buchanan. After switching to the steamer Philadelphia in Hampton Roads, they steamed up the Potomac. Thus, at around 11:30 AM on May 14, 1860, they found themselves at the quay of the Washington Navy Yard.

The whole city had followed the embassy’s progress for the last few days, and thus it was a huge crowd that was there. By 10:00 AM, there was a large number of people waiting, but it wasn’t until 11:30 that a single shot from a cannon indicated that the Philadelphia had been sighted down the Anacostia. This was the signal for all Navy Yard employees to down tools, exit their buildings and take up position.

They were joined by the Mayor of D.C., James G. Berret, and the members of the Common Council and Aldermen, who had been invited by Captain Buchanan, commander of the Navy Yard. Buchanan had also invited the members of the House of Representatives, but the usual bickering had kept them from passing a resolution that would have allowed them to be on hand. Instead, the embassy would have to make do with members of the Marines, as well as D.C. National Guard, the Montgomery Guard and various Cadet Corps.

As the ship docked, with one member of the embassy furiously sketching the assembled masses, a 17-gun salute was fired from some of the guns that had been taken from Britain during the War of 1812. Once the ship was tied up, Mayor Berret was the first to board it. Then the embassy disembarked, with Ambassador Shinmi Masaoki leading the way. After the members of the embassy set foot on land, the treaty itself was brought ashore. It had been, according to the May 14, 1860 Washington Evening Star,

“…enclosed in an oblong box some three feet in length, and of proportional width and depth, and covered with a red cloth. This was placed in a frame work of bamboo wood, through the top of which a pole some ten feet in length was thrust, a folding cover of wood was laid over the top, and with this novel arrangement borne in advance by two policemen.”

With everything and everybody now safely on dry ground, the assembled party proceeded to the commandant’s house, and from there onto carriages and omnibuses to take them to their hotel. They were followed “on all hands by the eager throng of spectators, number at least twenty thousand in all, whose curiosity had not abated one jot by the time the strangers arrived at their lodgings at Willard’s Hotel.”

Next week: A return to the Navy Yard.