Last week, I wrote about the building of the homes on Gessford Court and its rambunctious beginnings. Today, I will look at some of the people who lived on the Court and their stories.

Last week, I wrote about the building of the homes on Gessford Court and its rambunctious beginnings. Today, I will look at some of the people who lived on the Court and their stories.

Shortly after Charles Gessford’s death, and in hopes of quieting the alley, its name was changed to Gessford Street, and eventually, Gessford Court. This had little impact on the inhabitants, who continued to be known mainly for their rowdy behavior. The few times that Gessford is mentioned in the newspapers of the time, it is invariably in some unsavory connection, whether a knife fight or a particularly nasty death. Even when the news was not downright bad, it was hardly good. A news article from 1901, in the course of writing about a heat wave gripping the city, tells of a sweeper living in Gessford Court and working for the city post office who succumbed to the heat.

It did not help that the newspapers of the time reveled in describing exactly the sort of things that went on in Gessford Court. The front page of The Morning Times of November 15, 1896, takes great delight in telling of the tragic suicide of a Civil War veteran living in Gessford Court. The headline pretty much tells the whole story “Found the Body Hanging; Insane Colored Man Commits Suicide; Feet Touched the Floor; James T. Minor, a Veteran of the War, Ends His Life in a Tragic Manner-Tied a Rope to the Gas Jet, Stood on a Chair and Then Stepped Off.” It even includes a drawing showing the man doing the deed. Minor lived at 7 Gessford Court, where he plied the shoemaker trade, and had recently been released from St. Elizabeth’s hospital. The rest of the paper’s front page has articles about two further suicides, as well as a couple of murders and the arrest of a young man for reckless bicycling.

A year later, more noise was added to the alley, in the form of a blacksmith shop. Charles Prather, who had previously shared work premises at 1221 D St SE with his brother Ulysses, decided to strike out on his own. A stable next to 19 Gessford Court (or Getsworth, as it is written on the building application) was converted to this new industry.

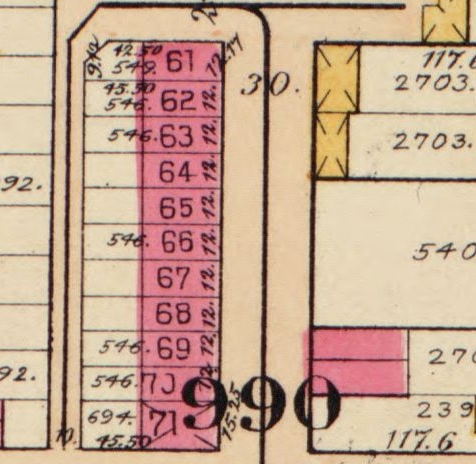

The 1900 census gives a good snapshot of life in, as the enumerator still insists on calling it, Tiger Alley. For one, it was remarkably crowded. Each of these little houses had at least four inhabitants, several had eight. Eleven of the 12 houses are enumerated, and they contain 63 inhabitants, for an average of almost 6 per household. The occupations listed are all labor-intensive: washing and ironing, laborer in a brick yard, day laborer, hod carrier, and servant are all shown. All but one were born in either DC or Maryland, the one exception was Virginia-born. And every one of them is African-American. The houses surrounding the Court show a very different story: Although they tended to be considerably larger, many houses have only two inhabitants, and although they are more crowded than would be the case today, they are not nearly as crowded as those on Gessford. The only exceptions are those rare houses in which African-Americans live; these have up to eight people living in them.

Newspaper accounts of the time continue to emphasize the less savory aspects of the alley. In 1922, a blind man living on Gessford told of being shot while attempting to get home, and in 1927, Mary Johnson was indicted on charges of having stabbed one Edward Marshall in Gessford Court. Things seem to have quieted down thereafter, and, after World War II, the only time Gessford made the news was when one or the other of the houses was for sale, a change which must have come as some relief to the inhabitants of the alley.

Next week: Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. – and the FBI – in Gessford Court.

Correction: I wrote last week that Charles Gessford had built Philadelphia Row, an error that is distressingly common, and one I that I have in the past avoided. The buildings on the east side of the 100 block of 11th street SE were, in fact, built by Stephen Flanagan. In a future column, I may delve into the origin of this persistent urban legend.

Shortly after Gessford’s death, and in hopes of quieting the alley, its name was changed to Gessford Street, and eventually, Gessford Court. This had little impact on the inhabitants, who continued to be known mainly for their rowdy behavior. The few times that Gessford is mentioned in the newspapers of the time, it is invariably in some unsavory connection, whether a knife fight or a particularly nasty death. Even when the news was not downright bad, it was hardly good. A news article from 1901, in the course of writing about a heat wave gripping the city, tells of a sweeper living in Gessford Court and working for the city post office succumbing to the heat.

It did not help that the newspapers of the time reveled in describing exactly the sort of things that went on in Gessford Court. The front page of The Morning Times of November 15, 1896, takes great delight in telling of the tragic suicide of a young man living in Gessford Court. The headline pretty much tells the whole story “Found the Body Hanging; Insane Colored Man Commits Suicide; Feet Touched the Floor; James T. Minor, a Veteran of the War, Ends His Life in a Tragic Manner-Tied a Rope to the Gas Jet, Stood on a Chair and Then Stepped Off” It even includes a drawing showing the man doing the deed. Minor lived at 7, Gessford Court, where he plied the shoemaker trade, and had recently been released from St. Elizabeth’s hospital. The rest of the paper’s front page has articles about two further suicides, as well as a couple of murders and the arrest of a young man for reckless bicycling.

A year later, more noise was added to the alley, in the form of a blacksmith shop. Charles Prather, who had previously shared work premises at 1221 D St SE with his brother Ulysses decided to strike out on his own. A stable next to 19 Gessford Court (or Getsworth, as it is written on the building application) was converted to this new industry.

The 1900 census gives a good snapshot of life in, as the enumerator still insists on calling it, Tiger Alley. For one, it was remarkably crowded. Each of these little houses had at least four inhabitants, several had eight. 11 of the 12 houses are enumerated, and they contain 63 inhabitants, for an average of almost 6 per household. The occupations listed are all labor-intensive: washing and ironing, laborer in a brick yard, day laborer, hod carrier, and servant are all shown. All but one were born in either DC or Maryland, the one exception was Virginia-born. And every one of them is African-American. The houses surrounding the Court show a very different story: Although they tended to be considerably larger, many houses have only two inhabitants, and although they are more crowded than would be the case today, they are not nearly as crowded as those on Gessford. The only exceptions are those rare houses in which African-Americans live; these have up to eight people living in them.