Looking through events other than those ending in death and which happened at the Washington Navy Yard in 1853, I came across a short article entitled “Resignation and probable Appointment.” In it, it stated that a James B. Elliott, “the efficient Engineer of the Copper Rolling Mill” had resigned.

There is no “James B. Elliott” listed in the 1853 guide to Washington, but there is a James P. Ellicott, listed as an engineer living on I street, just a few blocks from the Navy Yard Gate. The name is also intriguing, given the importance of another Ellicott in the early days of Washington, D.C.: Andrew Ellicott, who was responsible for turning L’Enfant’s plan into reality in the 1790s.

And indeed, it turns out that they are related: James P.’s great-great-grandfather is also Andrew’s grandfather, making them first cousins twice removed.

James P. Ellicott was born on August 22, 1826, the son of (a different) Andrew Ellicott and Emily McFadon Ellicott. He would marry Fannie Adelaide Ince on October 30, 1845. At the time of his resignation from the Navy Yard, the couple had three children, though one was to die the following year. They would eventually have four more, and a total of five would live to adulthood.

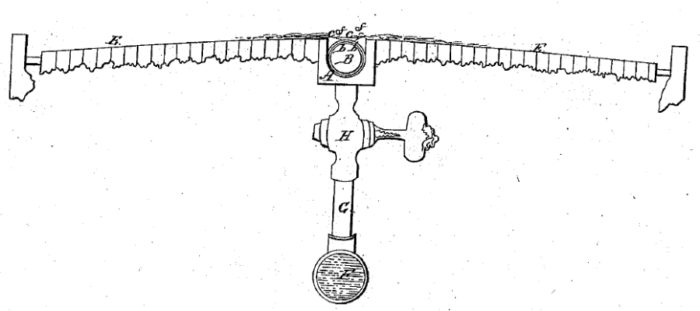

Ellicott, leaving the Navy Yard behind, would strike out in a very different direction, owning a billiard saloon near Pennsylvania Avenue on 13th Street northwest. However, he had not entirely forgotten his engineering roots, as in 1860, he became patent-holder of a patent for a new way of making billiard table pocket irons. The following year, he would patent a new way of installing street sprinklers, allowing for the easy cleaning thereof. He would expend a fair bit of energy trying to sell this over the next years, including having Senator William Pinkney Whyte of Maryland present a petition to have Pennsylvania Avenue be outfitted with this invention. There is no sign that this ever happened.

Ellicott’s greatest claim to fame actually came through his son, Henry Ellicott (pictured above)

The younger Ellicott was discovered as an artist in 1863, when he used new-fallen snow to create a bust of the newly-installed Assistant Secretary of the Interior, William Tod Otto, in front of the Ellicott house on F Street North. (Back then, they did not have the quadrant system– that was introduced post-Civil War, so the way you’d refer to streets would be “7th street east, near C Street south). The older Ellicot was induced to allow his son to pursue an artistic career. Henry Ellicott would create a number of sculptures, including several placed in Gettysburg, as well as the Winfield Scott Hancock statue erected on Pennsylvania Avenue, not far from his father’s billiard saloon, as well as some of the ethnographic heads in keystones above the many doors of the Library of Congress.

James Ellicott would return to his family roots later, taking over the operation of an iron furnace in Elkridge, Maryland after the Civil War. The furnace had belonged to his family previously, but they had sold it well before the war.

With that, Ellicott seems to disappear. He is listed as living in Baltimore in the 1870 census with his wife and children, but ten years later, there is no sign of him, and Fannie is listed as widowed.

I really do not wish to dwell on the vagaries of history here. I want to talk about the name of the man who had, in 1853, taken over from Ellicott at the Washington Navy Yard. The article is neither certain whether this person will, indeed, be given the job, nor do they know is whole name. They simply refer to him as “Mr. Bean” and leave us to wonder how much damage Rowan Atkinson would do while in charge of a hot, noisy, and dangerous copper rolling machine.