I wrote last week of Mrs. Mary Logan’s book Thirty Years in Washington. Today, I will look at what she wrote of a subject near to my heart: The Washington Navy Yard. She spends less than two pages on this important topic, starting with:

The Washington Navy Yard was established when the government was moved to Washington, and for more than half a century the largest and best men-of-war owned by the United States were constructed in its ship houses. With the advent of armored vessels of greater dimensions, however, conditions were so changed that, through two spacious ship houses remain, the work of this Navy Yard consists almost entirely of the manufacture of guns and ammunition and the storage of equipments.

After a long paragraph detailing the conversion of “great masses of iron” into finished guns, she continues with a description of the museum:

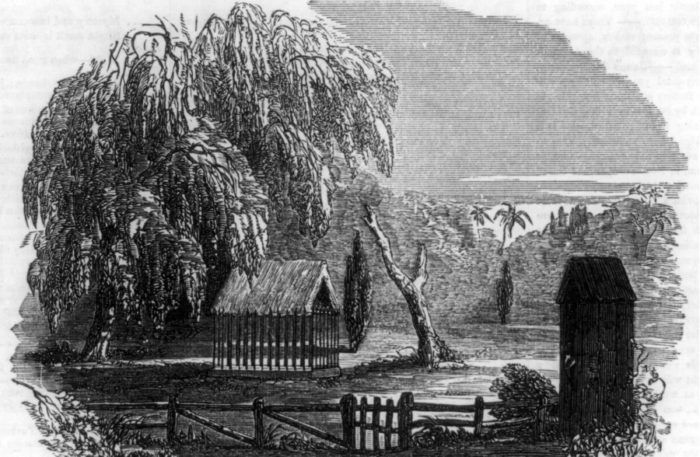

Entering the Naval Museum, which is shaded by a willow from a slip taken from one of the trees over the tomb of Napoleon at St Helena, we find ourselves surrounded with quaint forms of ordnance, and a multitude of relics of historic interest.

Multiple sources agree that the Navy Yard willow did, in fact, have its origins on St. Helena. Willows are easily propagated by cutting off a twig and simply planting it in the appropriate ground. Visitors to St. Helena after Napoleon’s death and interment in 1821 would then spread these far and wide. While most of these visitors were French, there were the occasional Americans as well. While sources differ on who was actually given the cutting that was planted at the Navy Yard, it was almost certainly an officer in the United States Navy. The two names usually mentioned are Commodore Bainbridge (pictured) and Admiral Lanman.

William Bainbridge served in the Navy from 1798 until his death in 1833. He was in St. Helena – but in 1812, well before Napoleon’s exile there, to say nothing of his death. Joseph Lanman served during the Civil War, then was in command of the South Atlantic fleet for many years, making it much more likely that he would have stopped by St. Helena. In short, however, it is clear that there is no way to determine the true provider of the tree.

The tree must have done well in its new location, and some years later, a cutting from it was brought to Mount Vernon and planted overlooking Washington’s tomb. From there, the tree spread far and wide. One such descendant continues to thrive in Washington state. While Mount Vernon has confirmed that the Napoleon Willow that was planted at Washington’s tomb is no longer living, the fate of the Navy Yard tree is less clear. A 1912 article written by one George Clinton (no, not that one. Or this one) and published in numerous newspapers around the country claims that it is still “hale and hearty in its willowy old age.”

One thing is certain: the museum of which Mrs. Logan writes moved twelve years after she wrote about it, and found its current home in 1935, and thus the Napoleon Willow certainly no longer shades the entrance to the museum; the land on which the museum stood in 1901 has just a few smaller trees on it, almost certainly none of which can trace their lineage back to the tree shading Napoleon’s tomb.