When we think of what the government does today, we think in terms of abstract things: Laws, regulations, standards.

When we think of what the government does today, we think in terms of abstract things: Laws, regulations, standards.

In the 19th century, however, government was on occasion more concrete. For instance, a pound today is determined in terms of the kilogram (which, in turn, is determined by the weight of water and the length of a meter) Back then, however, the pound was defined by a reference weight that was deposited in the British Standards department. Since not everyone could make their way there to see if their weights were correct, it fell to the United States to make reference weights in order to make sure that everyone was using the same scale.

In 1833, a law was passed that said that everyone should use the same weights, and that each state should have a reference weight. This required casting brass ingots of the appropriate size. In order to do this, the government turned to John Hitz (pic) to make the best possible brass for this purpose.

Hitz was a mining engineer, and since his arrival in the US from Switzerland in 1831 had worked at a number of Virginian gold mines, opening them and directing them. He was therefore well-suited for the task at hand, and, in particular, to find the best zinc. He was working at the Arsenal at the time, and was given a ‘caster’ to work with on this.

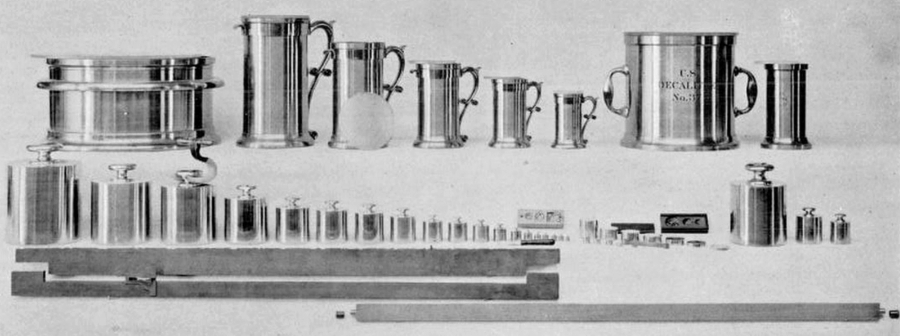

A set of reference weights and measures of the type that Hitz assisted with (Google Books)

Hitz traveled around the country to find the appropriate zinc, then returned to D.C. to cast the weights. After the ingots had been delivered, he continued to work in D.C., until 1853, when he was appointed the Consul General of his native Switzerland. He was well-known and liked across the city in this capacity, and with the beginning of the Civil War, he found himself in a new role, as described by John P. Usher in his 1925 book President Lincoln’s Cabinet:

Occasionally a countryman of his would enter the army, and finding the service uncomfortable, would apply to Hitz to get him discharged. Hitz would make the appeal, but generally concluded by saying that if the ground stated by him did not compel the discharge of the soldier, he wanted him to stay and fight – that the Swiss were a liberty loving people and could never be better employed than fighting for it.

According to his obituary, published in the Washington Evening Star, his assistance to his countrymen extended even beyond this:

He had the confidence of the soldiers to such an extent that hundreds of them would regularly send their money to him, as a sort of banker.

Sadly, Hitz did not see the end of the war, dying in 1864. His funeral, which took place at his home on A Street SE –just southeast of the Capitol– was attended by a wide variety of important people in D.C., including Ministers from Russia, Spain, the Hanseatic League, Sweden, Belgium, Brazil, and Portugal. Rounding out the dignitaries was none other than President Lincoln himself, accompanied by several members of his cabinet, including William Henry Seward. Hitz was buried in Congressional Cemetery.